Safe Work Method Statements (SWMS) in New Zealand – What the Law Actually Requires

Safe Work Method Statements (SWMS) are not explicitly required by law in New Zealand, but the outcomes they are often used to achieve absolutely are.

Under the Health and Safety at Work Act 2015 (HSWA) and supporting regulations, PCBUs must identify risks, implement controls using the hierarchy of controls, and ensure workers understand how work is to be done safely.

A SWMS can be one way of meeting those obligations – but it is not a legal substitute for proper risk management, nor is it mandated in the same way as in Australia.

This distinction matters, and misunderstanding it is where many businesses get into trouble.

Are SWMS a Legal Requirement in New Zealand?

No – SWMS are not specifically mandated under HSWA or its regulations.

However, PCBUs must:

Identify reasonably foreseeable risks

Eliminate risks where practicable

Minimise remaining risks using effective controls

Ensure workers understand how to carry out work safely

Review controls when conditions change

WorkSafe guidance makes it clear that documents are not the goal – effective risk management is.

SWMS may be used as an administrative tool to support these duties, particularly for complex or high-risk work, but relying on a SWMS alone does not meet legal obligations.

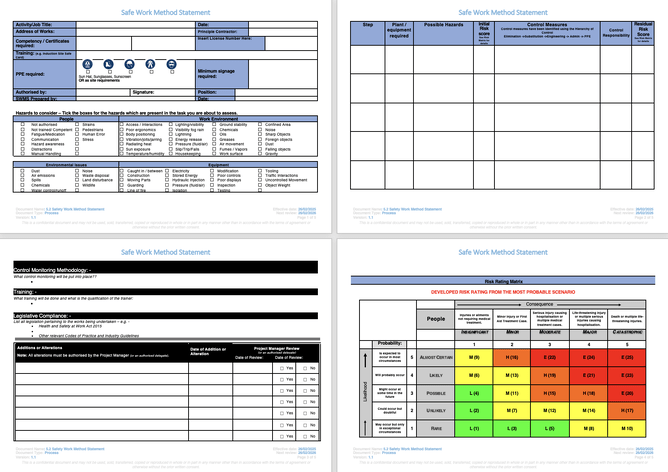

What Does A SWMS Look Like?

What Is a Safe Work Method Statement (SWMS)?

A Safe Work Method Statement (SWMS) is a task-based document that typically:

Describes a specific work activity

Identifies hazards associated with that task

Outlines control measures to manage those risks

Communicates how work should be carried out safely

In New Zealand, SWMS are most commonly used in construction and infrastructure work, particularly where contractors are familiar with Australian systems or client-driven requirements.

Importantly, a SWMS is classified as an administrative control under the hierarchy of controls – it does not replace higher-order controls such as elimination, isolation, or engineering.

Why SWMS Are Commonly Used for High-Risk Work

Although not legally required, SWMS are often used to support work involving:

Working at height

Excavations and trenches

Powered mobile plant

Confined spaces

Work near live services or traffic

Complex sequencing or contractor interfaces

In these situations, a SWMS can help communicate risk controls clearly, particularly where multiple parties are involved.

That said, WorkSafe does not recognise SWMS as a standalone compliance document.

SWMS vs NZ Legal Requirements – The Critical Difference

This is where many businesses get it wrong.

Under NZ law, PCBUs must ensure:

Risks are assessed in context

Controls are selected using the hierarchy of controls

Workers are trained and supervised

Controls are monitored and reviewed

WorkSafe guidance emphasises that generic or templated SWMS are often ineffective, especially when:

Site conditions change

Work methods vary

Infrastructure is modified

New hazards are introduced

If a SWMS exists but does not reflect how work is actually done, it offers little protection during an investigation.

What WorkSafe Expects Instead of “Just a SWMS”

What WorkSafe Expects Instead of “Just a SWMS”

WorkSafe NZ guidance aligns risk management with:

Task-specific risk assessment

Practical control selection

Worker engagement

Ongoing review

In practice, this often looks like:

A task risk assessment (TRA/JSA/TA)

Site-specific control planning

Clear work instructions

Toolbox discussions

Supervisor verification

Review when conditions change

A SWMS may form part of this system, but it is not the system itself.

Key Elements of an Effective SWMS (If You Use One)

If your organisation chooses to use SWMS, WorkSafe-aligned best practice includes:

Clear description of the specific task

Hazards linked to the actual site and conditions

Controls prioritised using the hierarchy of controls

Defined responsibilities for implementation

Evidence that workers understand the controls

Review triggers when work conditions change

Overly detailed, generic, or “tick-box” SWMS often create false confidence rather than real safety.

Who Should Be Involved in Preparing a SWMS?

An effective SWMS should never be written in isolation.

Best practice involves:

The PCBU responsible for the work

Workers performing the task

Supervisors overseeing the activity

Health and Safety Representatives (where applicable)

Worker involvement is particularly important – not as consultation theatre, but to ensure controls are practical and workable.

Implementing a SWMS Properly

A SWMS only adds value if it is actively used.

That means:

Workers understand it before work starts

Supervisors verify controls are in place

Conditions are checked continuously

Work stops if controls are no longer effective

The document is reviewed when circumstances change

A SWMS sitting in a folder or prequal portal offers no legal protection.

Can a Generic SWMS Be Used?

Only as a starting point – never as the final control.

Generic SWMS often fail because they:

Miss site-specific hazards

Assume conditions that don’t exist

Over-rely on PPE

Ignore sequencing or interfaces

WorkSafe has repeatedly highlighted that generic documents do not meet the “reasonably practicable” test if risks are foreseeable.

Final Word on SWMS in New Zealand

Safe Work Method Statements are not legally required in New Zealand – but effective risk management absolutely is.

A SWMS can support that process when:

It reflects real work

It prioritises higher-order controls

It is actively implemented and reviewed

But no document will compensate for:

Poor risk assessment

Outdated controls

Unchecked assumptions

Lack of supervision

If you are unsure whether your current approach genuinely meets HSWA expectations – particularly for high-risk or changing work – this is where an independent, under-the-hood review adds real value.